Techniques

Underglaze Blue

Skillful detailing and shading create naturalistic images

technique

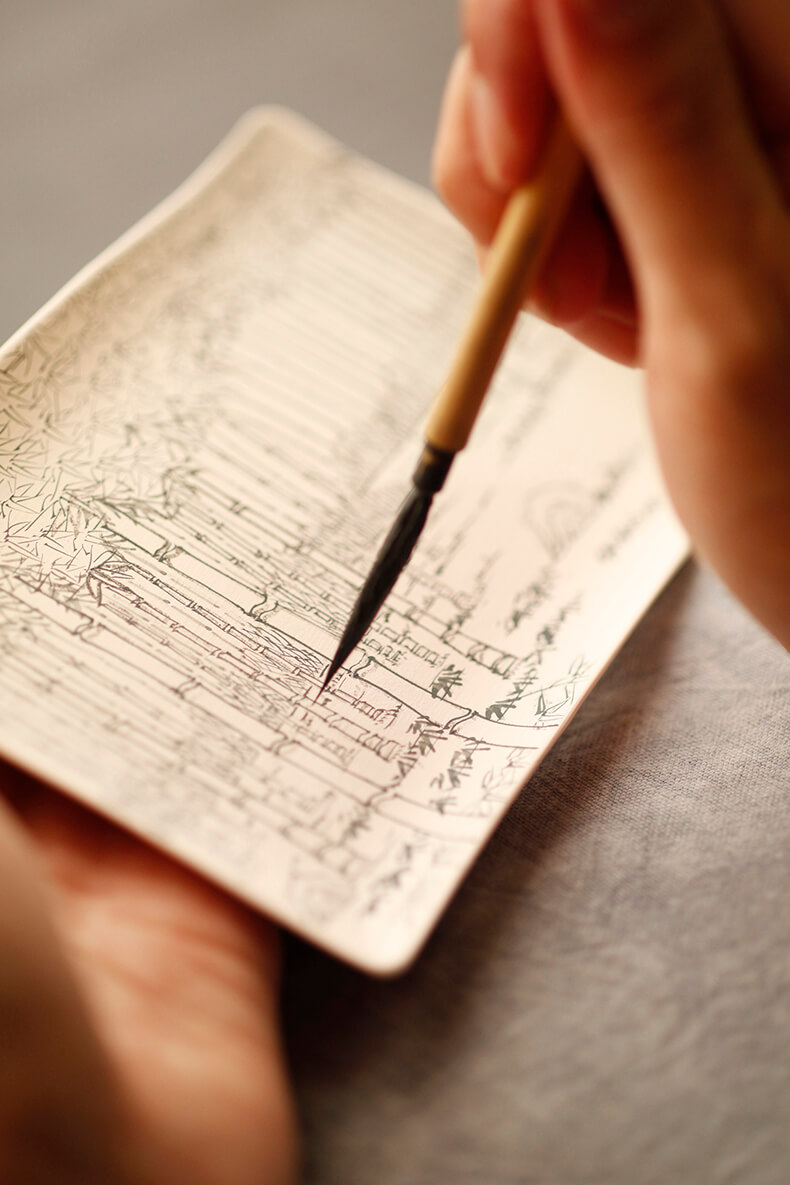

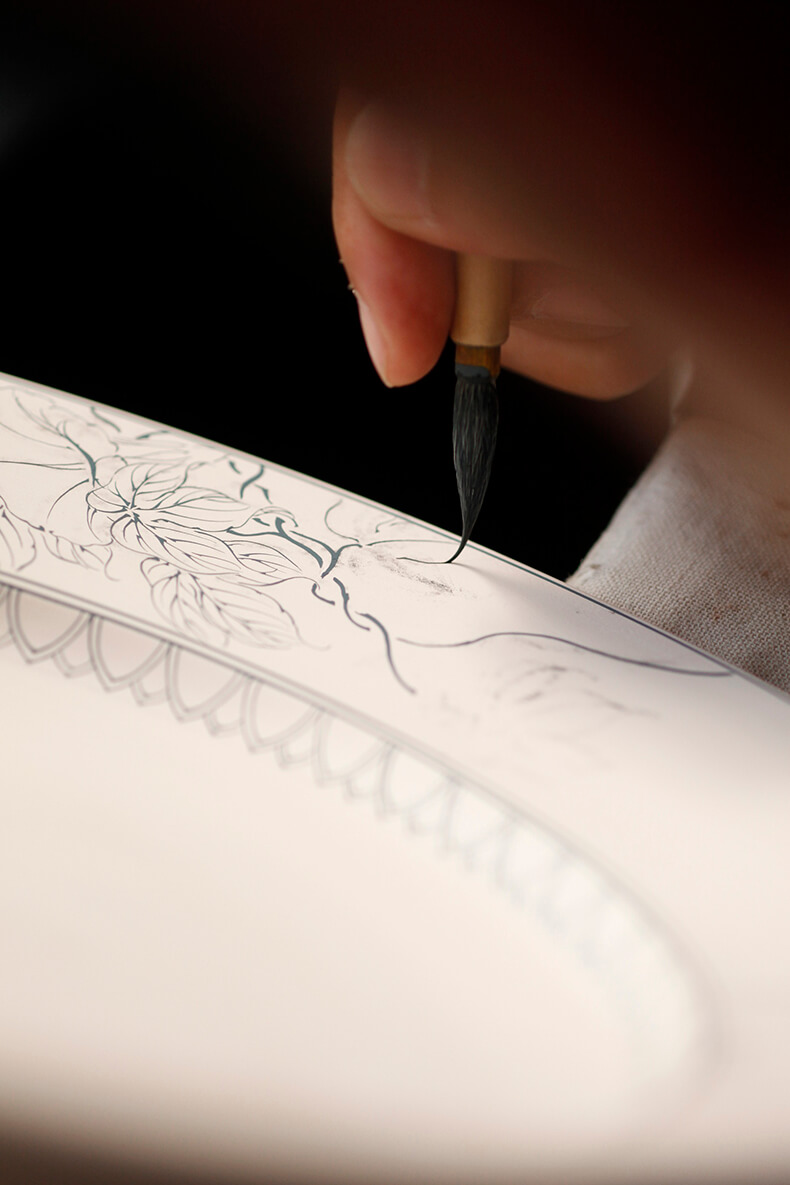

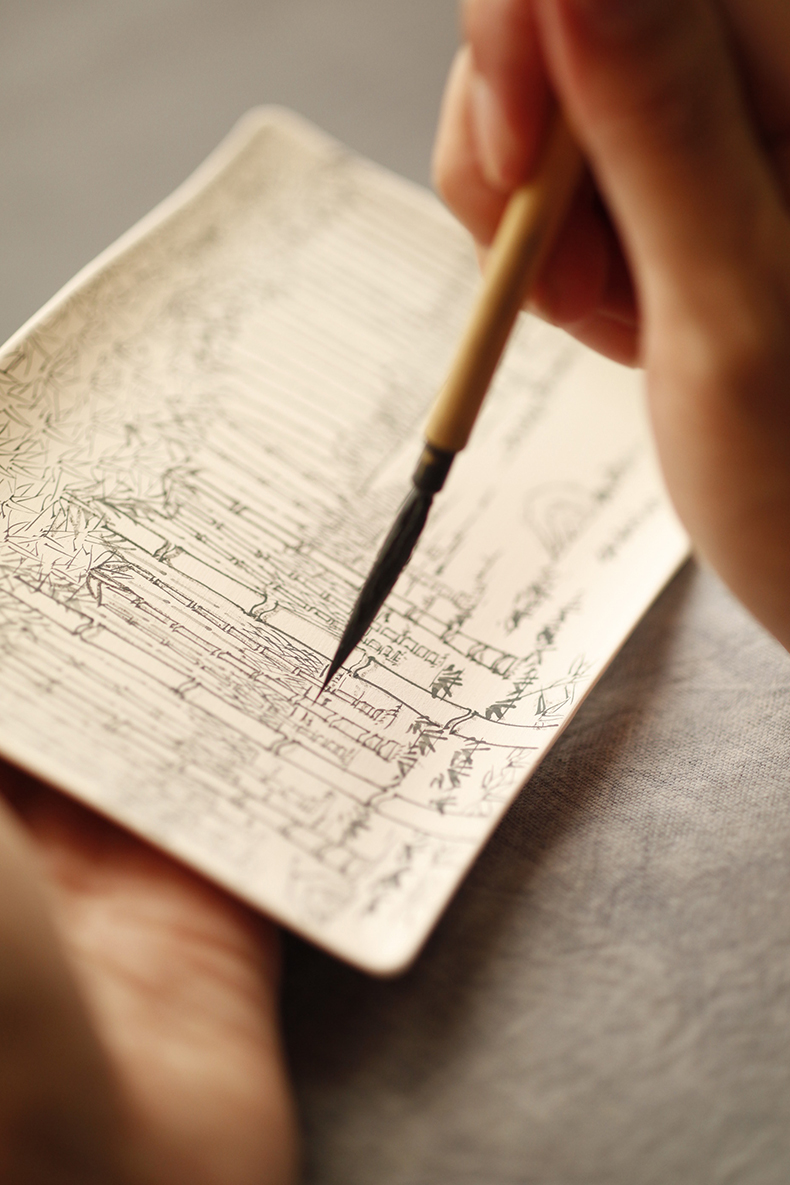

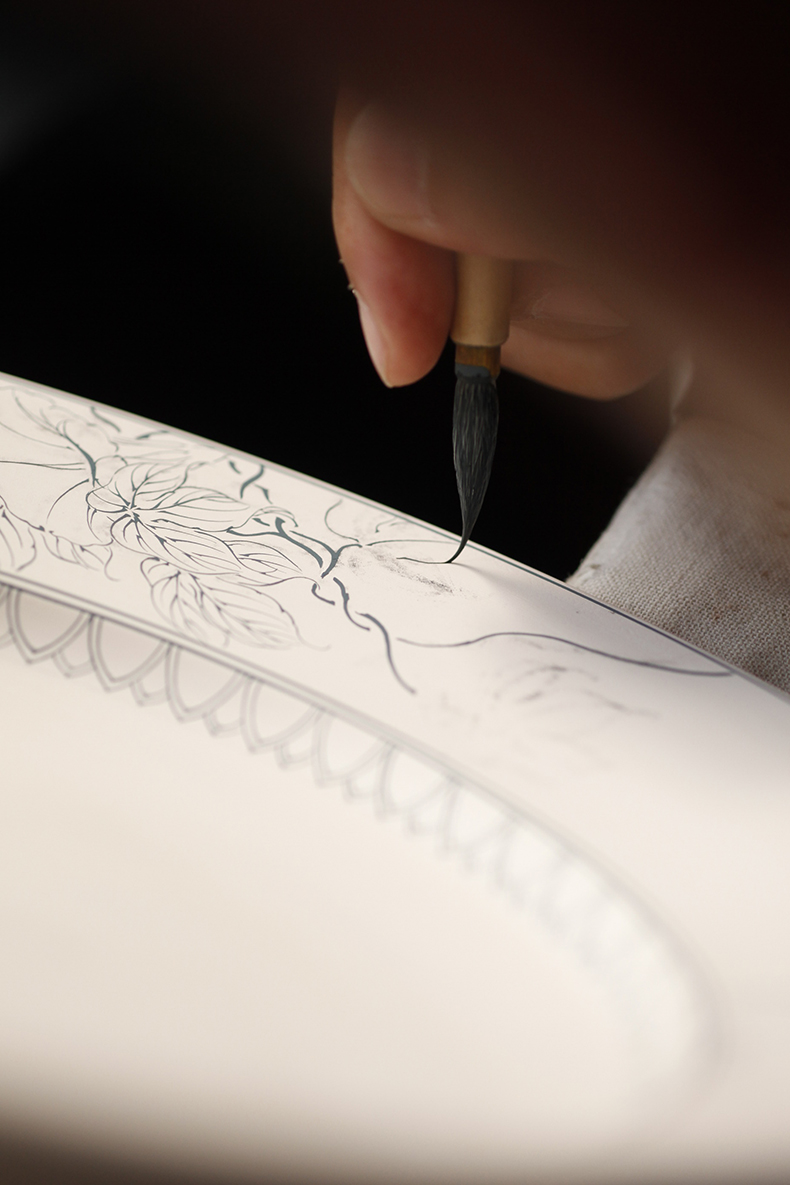

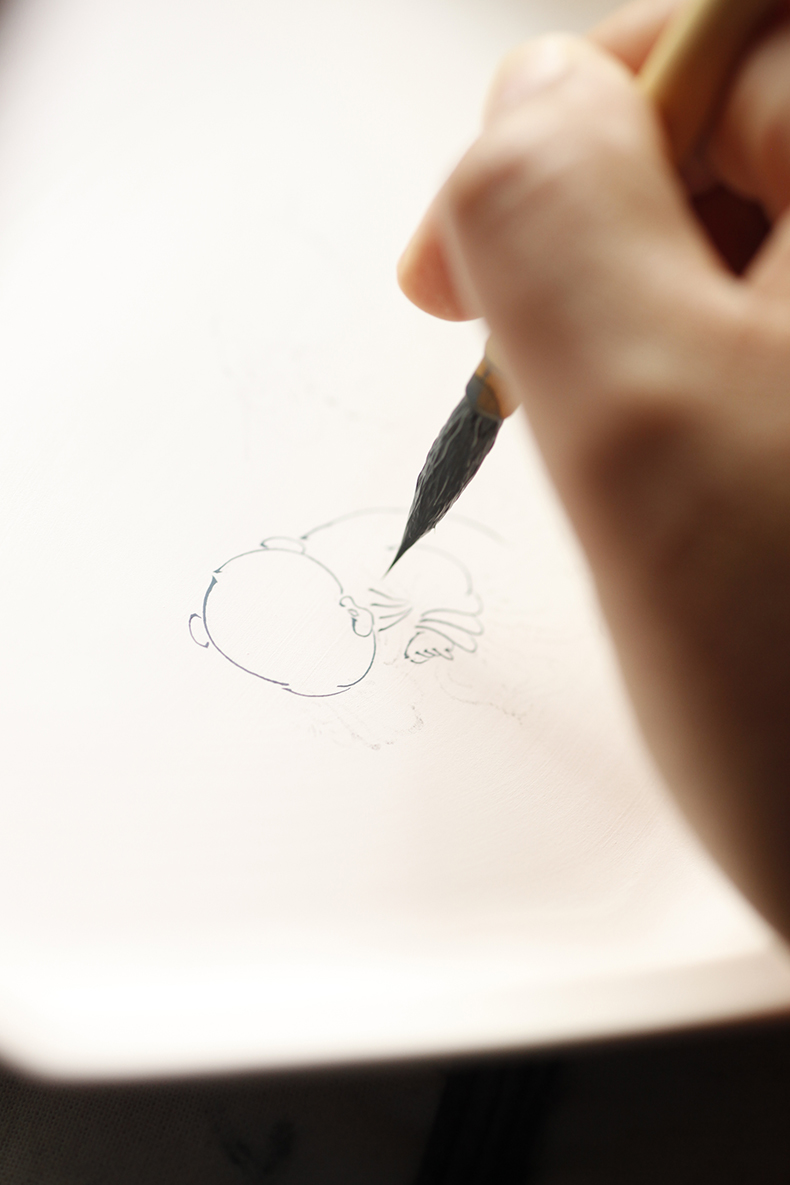

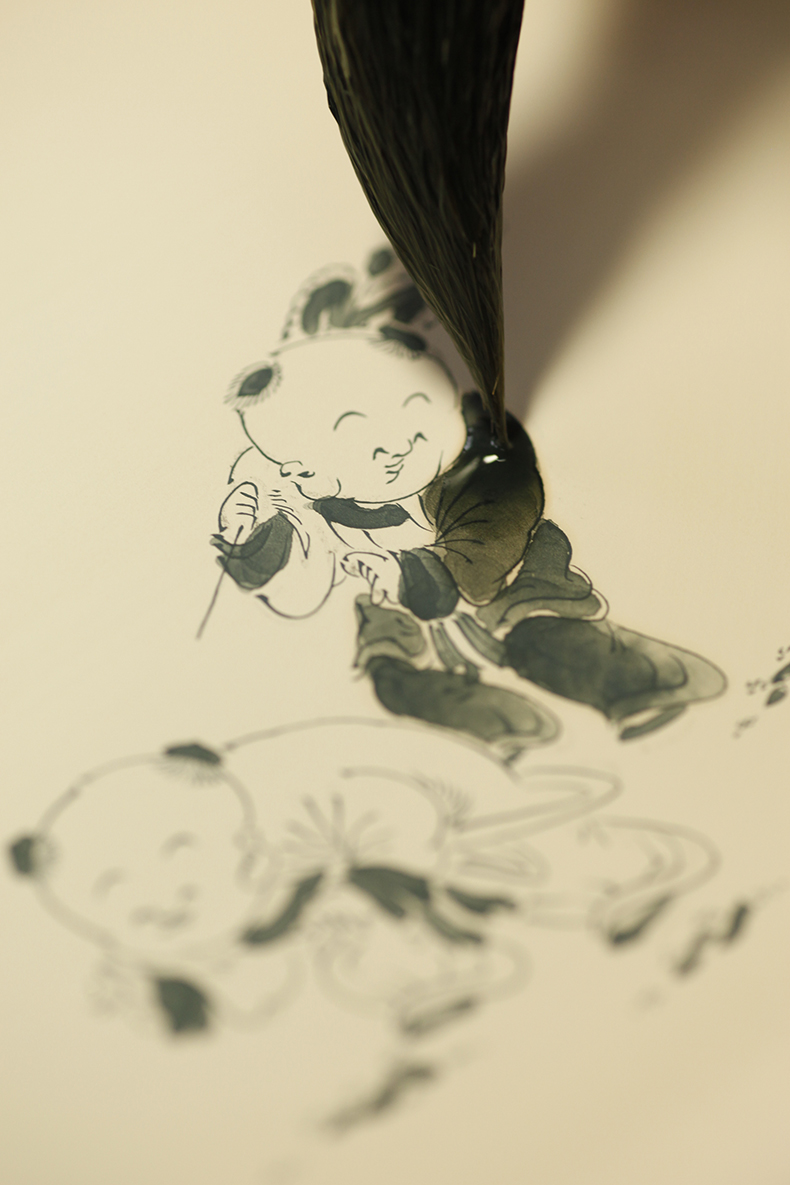

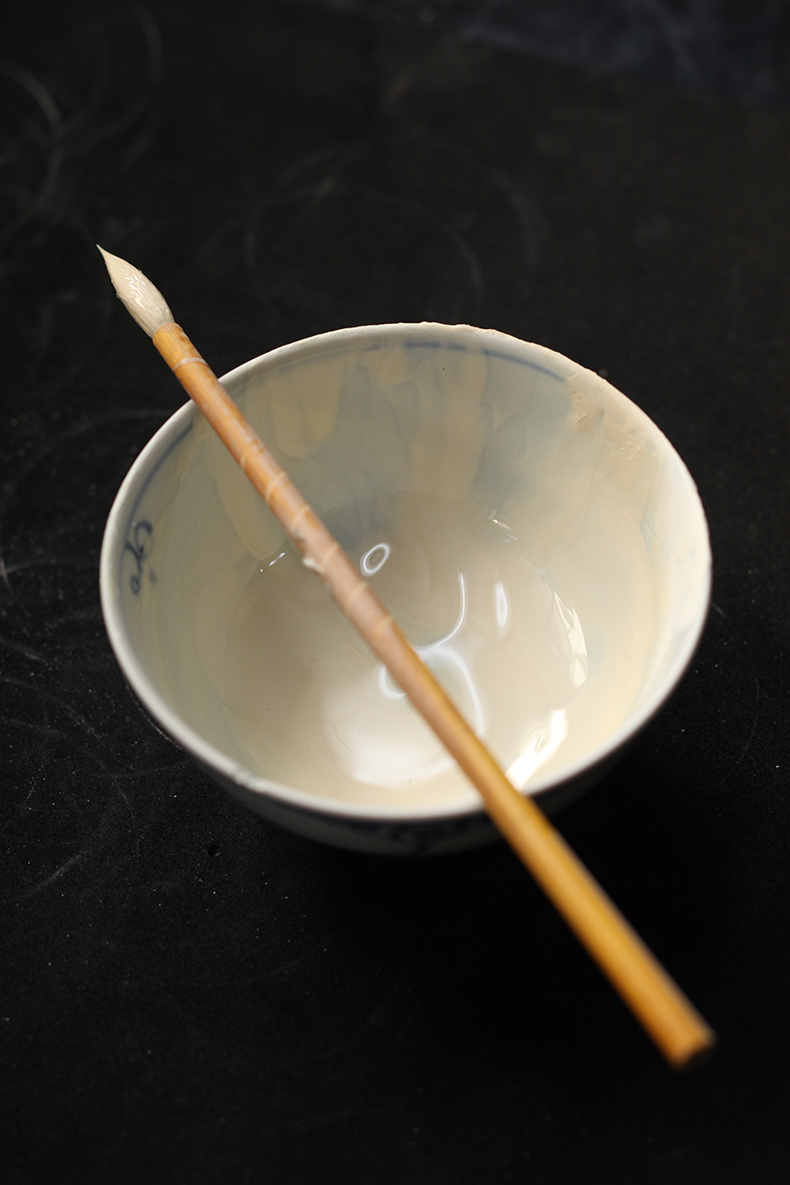

This is a technique of painting indigo-colored designs onto a white bisque surface using a brush soaked in cobalt blue pigment called gosu. The process of painting the outline of motifs onto bisque-fired pieces and adding color is called etsuke. Filling in the outlined areas with cobalt blue pigment is specifically known as dami. The pot is turned on its side, and a special dami brush steeped in gosu is used to drip the colored pigment so it soaks into the horizontal surface. The bare bisque surface is highly absorbent, so it is necessary to keep the dami brush constantly in motion.

Feature

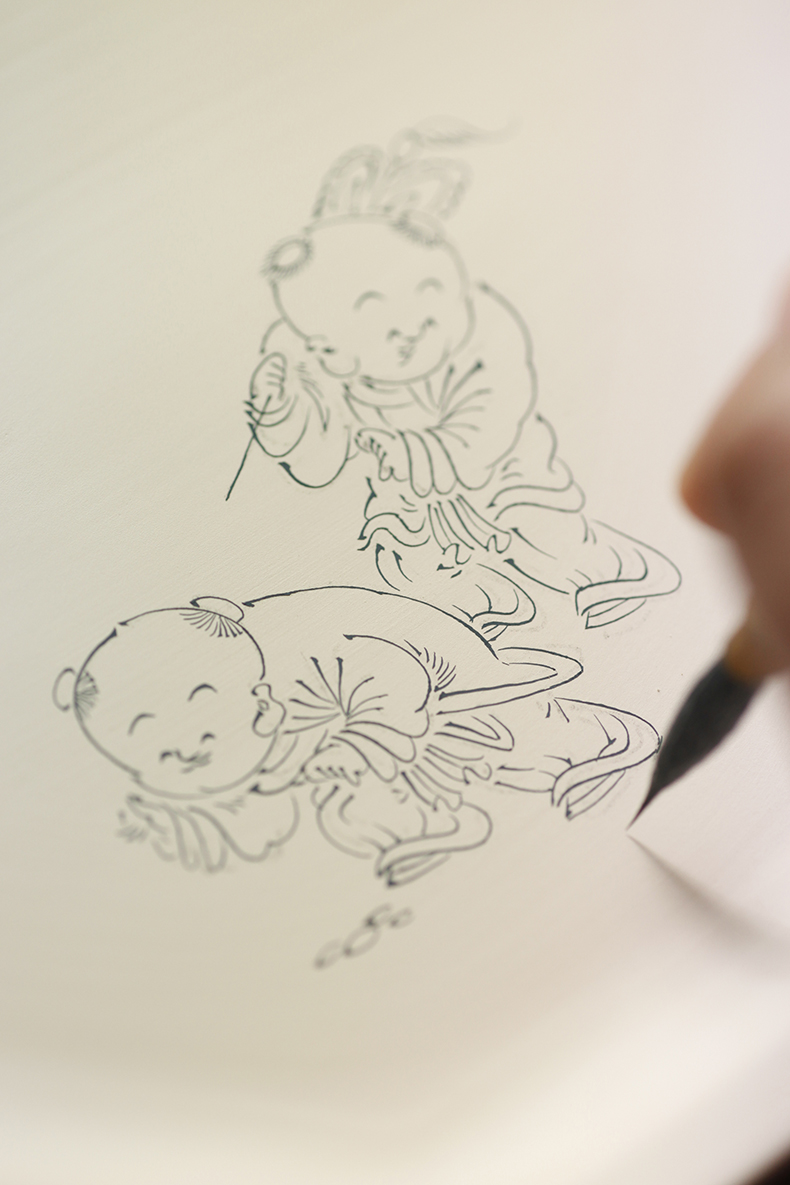

Underglaze blue work at Mikawachi is described as being “just like a painting.” When applying images to pottery, abbreviations and changes occur naturally as the artist repeats the same motif many times over – it becomes stylized and settles into an established “pattern.” At Mikawachi, however, the painted designs do not pass through this transformation; they are painted just as a two-dimensional work, brushstroke by brushstroke. This is why painterly techniques, like color gradation in the cobalt pigment expressing solidity and perspective, continue to play an important role.

Children at Play

Children Playing Happily: Symbols of Prosperity

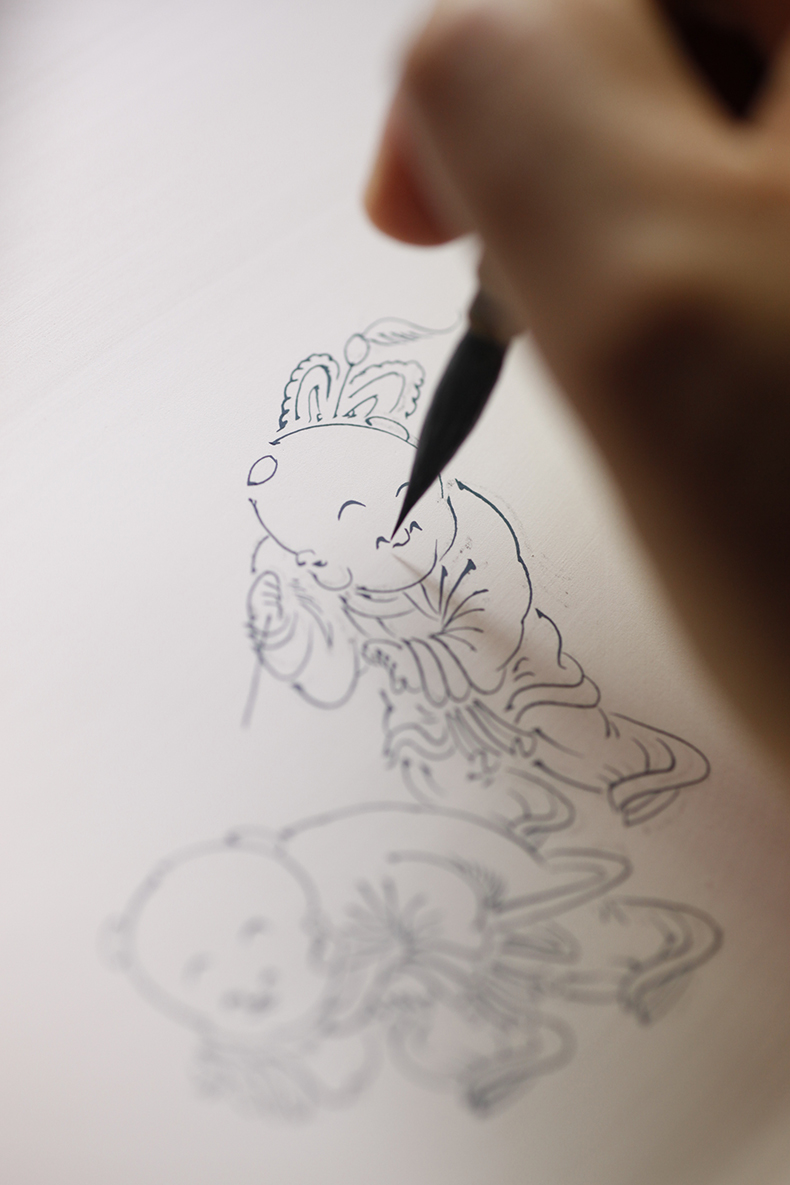

Cute Chinese children, playing joyfully, are a characteristic motif found on Mikawachi ware. In China the birth of a boy is considered a symbol of good fortune, and children at play – suggestive of happiness and prosperity – have been used as a painting subject since the Tang Dynasty (8th century). In the Ming Era (1368-1664), around the time that Japanese Mikawachi ware was first developed, Chinese artists often used underglaze blue or overglaze polychrome enamels to portray this subject on ceramics.

At Mikawachi, Tanaka Yohee Naotoshi, painter for the Official Kiln, is said to have adopted the motif from Ming Chinese underglaze blue ware around 1661. One well-known scene shows Chinese children frolicking with butterflies under a pine tree. Apparently the daimyō-sponsored workshop also produced dishes depicting Chinese children together with Taihu stones (porous limestone) and peonies, and a linked chakra (royal wheel) motif around the rim.

In the Meiji period (from 1868) painters began to add their individual touches to the Chinese child design, and their expressions and appearance varied a lot. These joyful, appealing children’s images continue to be produced to this day.

Eggshell porcelain

Translucent Vessels Full of Tense Fragility

This is very fine ceramic ware of less than a millimetre in thickness which shines like a bulb when held up to a light source.

Lightweight, thin ceramics have been made at Mikawachi since the end of the Edo period (mid 19c); best known are the lidded rice bowls and coffee cups produced for export. These were known by the Chinese term botai (pronounced hakutai in Japanese) or rankakude, taken from the English name ‘eggshell’.

It is very rare to find painted decoration on eggshell porcelain because any moisture from the paint absorbed by the unglazed surface would disturb the balance of the piece and cause warping. This illustrates the extreme delicacy of the vessels.

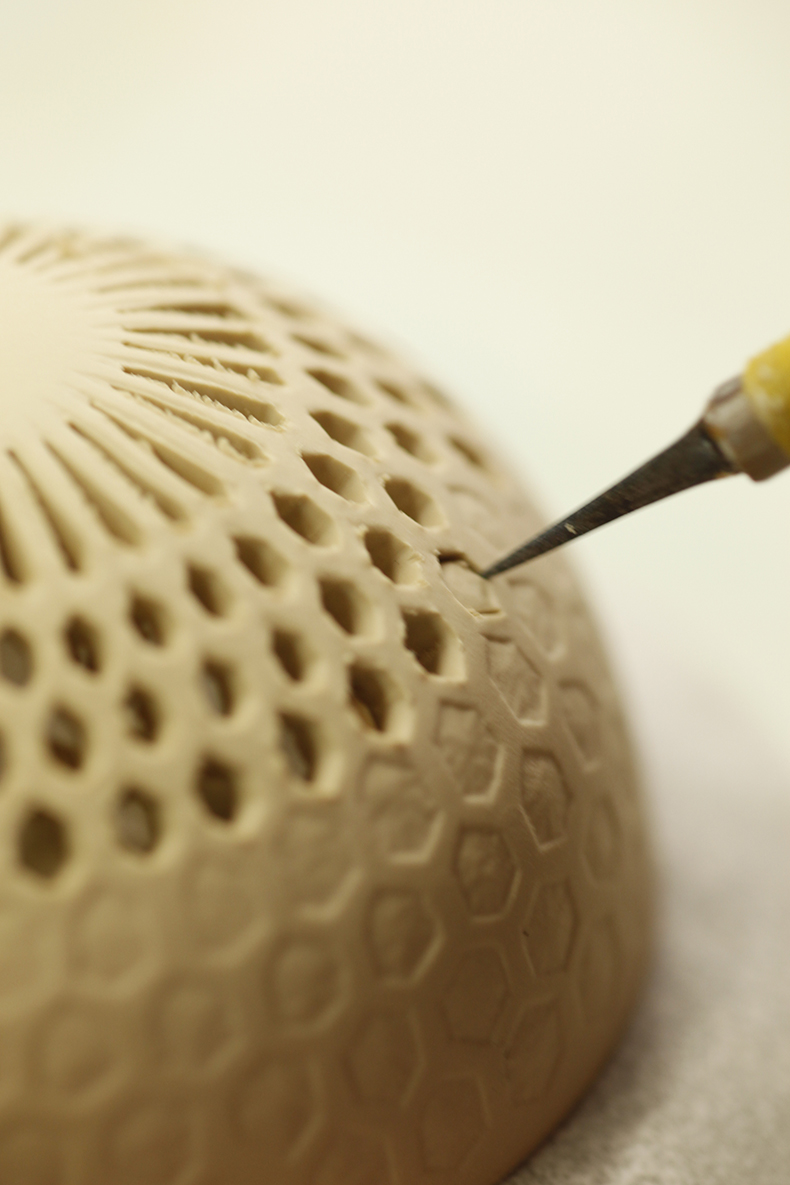

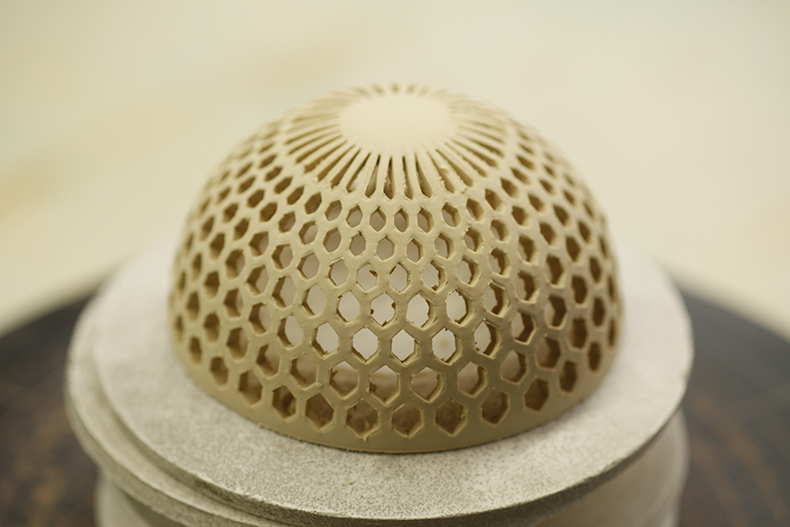

Openwork Carving

Light, Airy, Stylish Workmanship

Openwork is a type of traditional workmanship using an intricate technique where parts of the surface are carved out to create the pattern. The entire openwork design has to be carved directly out of the body of the piece before the clay dries out, but each new perforation in the clay makes the form more unstable, so the work has to proceed with a very careful calibration of the overall balance.

This process does weaken the pot itself; Mikawachi has developed openwork to the limits of what is possible, carving out the entire surface of a pot in the manner of basket-weave. From the 17th century right through to the 19th and early 20th centuries, Mikawachi artists continued to create pieces with ever more complex techniques.

Relief Work

Building Up Layers - Making Solid Ceramics Look Soft

This relief-work technique known as okiage is used to apply three-dimensional designs to vessels; it is an ancient Japanese technique found in Muromachi period (14th to 16th century) Seto ware from Aichi prefecture, and Momoyama period (late 16th century) Raku Ware from Kyoto prefecture.

At Mikawachi okiage is produced by applying layers of diluted white slip with a brush to gradually build up the image. It is characterised by velvety smooth lines and textures, like layers of soft fabric on the hard porcelain surface. Perfected in the Meiji period (1868- 1912), it was used on jars and bowls during the Taishō (1912-26) and early Shōwa periods (1926-1989).

Hand-Crafted Chrysanthemums

A White Flower Emerges as Each Petal is Carved Out

The ceramic chrysanthemum flower is one type of hand-crafted decorative element. Using a sharp-tipped bamboo tool, the shapes of the flower petals are cut out one by one from a lump of clay. Once the artist has a circle of petals, these are then carved in high relief. This process is then repeated several times to create the chrysanthemum form which is attached to jars, plates and bottles as decoration.

When carved, the individual petals stand up very sharply, but once the piece has been glazed and fired it softens to take on the appearance of a natural chrysanthemum.

Hand-Forming

Adding the Vitality of Animals and Plants to Pottery

Mikawachi kilns use decorative techniques where shapes are created in the same clay as the base clay, using a variety of hand-crafted methods. Mikawachi potters create realistic, lifelike animals and plants which spring from the surfaces of the pots. Dragons, lions and chrysanthemums are among the motifs which have been passed down from one generation to the next, to be used not on tableware but on ornamental pieces.

These flourished throughout the 19th and beginning of the 20th century; in the Edo period (until 1868) these were made as offerings and gifts from the Hirado clan, and after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 a large number were produced to exhibit at International Expositions as a display of technical achievement.

Overglaze Decoration

After a blue-and-white piece is glaze fired at around 1300° C, red, green, yellow, or gold enamels are applied to the glazed surface. The piece is then fired at a low temperature (600°-800° C, depending on the fusing temperature of the enamel). Although Mikawachi ware was primarily blue-and-white pottery with underglaze cobalt decoration, as exports became popular in the late Edo and Meiji periods, Mikawachi potters began to add red and gold overglaze decoration to their ware.